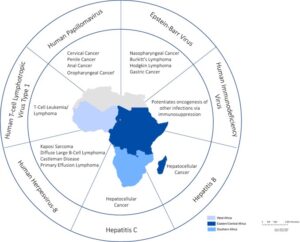

Cancer has rapidly emerged as a major public health concern in Africa, where the dual burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases is straining already limited healthcare resources. Viral infections contribute significantly to this burden. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that infection-associated cancers account for up to 30–40% of all cancer cases in sub-Saharan Africa, compared to less than 10% in most high-income regions (WHO, 2023).

Among these infectious agents, three stand out as persistent oncogenic culprits: Human Papillomavirus (HPV), Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV), and Hepatitis B Virus (HBV). Each is capable of integrating into the host genome, disrupting normal cellular regulatory mechanisms, and driving tumorigenesis through distinct molecular pathways. These viruses not only initiate malignancy but also shape disease outcomes through their genetic diversity and molecular evolution, especially within African populations where host genetics, immune pressures, and environmental cofactors interact uniquely.

Over the past decade, advances in molecular biology and next-generation sequencing (NGS) have revolutionised our understanding of how viral genotypes, sublineages, and mutations influence cancer risk and therapeutic response. However, the African continent remains underrepresented in global genomic databases, which limits the ability to design effective vaccines, diagnostics, and treatment strategies tailored to local viral diversity (Ogembo et al., 2015; Chang et al., 2009).

We take an integrated look at the molecular characterisation, epidemiology, and clinical implications of HPV, EBV, and HBV in African cancer patients. It highlights the pressing need for molecular surveillance, genomic research infrastructure, and regional data-sharing networks to support precision oncology in Africa.

Figure 1: Geographic Distribution of Major Oncogenic Viral Genotypes in Africa.

HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS (HPV): THE MOLECULAR SIGNATURE OF CERVICAL CARCINOGENESIS EPIDEMIOLOGICAL BURDEN IN AFRICA

Cervical cancer remains the most prevalent cancer among women in sub-Saharan Africa, responsible for more than 100,000 new cases and 70,000 deaths annually (IARC, 2021). Persistent infection with high-risk HPV types is the established cause, with HPV16 and HPV18 accounting for about 70% of global cases. However, the African epidemiological landscape is characterised by a broader diversity of high-risk genotypes, including HPV35, HPV45, HPV52, and HPV58, which appear more prevalent in West, Central, and East Africa (Okoye et al., 2021).

Socioeconomic factors, limited screening, early sexual debut, and co-infections (particularly with HIV) contribute to higher infection persistence rates and rapid progression from precancerous lesions to invasive carcinoma (de Vuyst et al., 2012).

Molecular Pathogenesis and Oncogenic Mechanisms

HPV’s oncogenic potential lies in the activity of its two transforming oncoproteins, E6 and E7, which disrupt host tumour suppressor pathways. The E6 protein promotes ubiquitin-mediated degradation of p53, a critical guardian of genomic integrity, while E7 binds and inactivates retinoblastoma protein (pRb), pushing cells into uncontrolled replication (Münger et al., 2004).

The virus’s circular double-stranded DNA genome (~8 kb) comprises early (E1–E7) and late (L1, L2) genes, and molecular variants within these regions alter pathogenicity. Mutations or polymorphisms in E6/E7 have been linked to differences in transformation efficiency, immune escape, and clinical outcomes.

Genetic Variability of HPV in African Populations

HPV16 exhibits four major lineages (A–D) and multiple sublineages (A1–A4, D1–D4). African isolates commonly fall into lineage A4 and sublineages D2/D3, both associated with increased persistence and cancer risk (Cornet et al., 2013). Similarly, HPV18 shows a higher prevalence of the African (AfR) variant, which carries unique mutations in the L1 and E6 genes that may influence vaccine efficacy and immune recognition (Chen et al., 2015).

Molecular studies across Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa have revealed region-specific genotype clustering, suggesting localised viral evolution driven by host genetic diversity and environmental pressures. For instance, HPV35, rarely seen in Europe, is strongly associated with invasive cervical carcinoma in Nigerian and Ghanaian cohorts (Ogembo et al., 2015).

Implications for Vaccination and Diagnostics

The currently available HPV vaccines (Cervarix, Gardasil, and Gardasil 9) target major high-risk types, but do not fully cover the diversity of African variants. Molecular characterisation is therefore essential to assess cross-protection and identify gaps in vaccine coverage. Genomic surveillance can also support molecular diagnostic development, ensuring that PCR-based or hybrid capture assays recognise local viral sequences without false negatives.

EPSTEIN–BARR VIRUS (EBV): MOLECULAR EVOLUTION AND ONCOGENIC LATENCY EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CANCER ASSOCIATIONS

EBV, a member of the Herpesviridae family, infects over 90% of the global population, typically persisting for life in B lymphocytes. In Africa, early childhood infection is nearly universal, but certain EBV variants and co-factors (e.g., malaria, HIV) dramatically increase the risk of Burkitt lymphoma (BL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) (Chang et al., 2009).

Burkitt lymphoma, first described in Ugandan children, remains the most common pediatric cancer in equatorial Africa, where EBV-positive cases approach 95% prevalence (Magrath & Bhatia, 1992).

Molecular Structure and Latency Programs

EBV’s 170–180 kb double-stranded DNA genome encodes multiple latency-associated proteins (EBNA1–6, LMP1–2) and noncoding RNAs that reprogram host cells. The virus alternates between latent and lytic infection states, with latency types I–III determining the expression pattern of viral genes in tumours.

- Latency I, typical of Burkitt lymphoma, expresses EBNA1 only.

- Latency II, seen in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, expresses EBNA1, LMP1, and LMP2.

- Latency III, characteristic of immunosuppressed patients, expresses the full latency gene set.

The switch between these programs depends on epigenetic regulation of viral promoters, host immune pressure, and co-infection dynamics (Young & Rickinson, 2004).

Table 1: EBV Latency Programs and Associated Malignancies in African Populations.

| LATENCY TYPE | VIRAL GENES EXPRESSED | ASSOCIATED MALIGNANCIES |

| LATENCY I | EBNA-1 | Burkitt’s Lymphoma |

| LATENCY II | EBNA-1 | Classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Undifferentiated Carcinoma Peripheral T/NK Cell Lymphoma |

| LMP1 | ||

| LMP2 | ||

| BARF0 | ||

| LATENCY III | All EBNAs | AIDS-associated Lymphomas

Post-transplant Lymphoproliferative disorders |

| EBERs | ||

| LMP1 | ||

| LMP2 | ||

| BARF0 |

Genetic Diversity of African EBV Strains

EBV exists as Type 1 and Type 2 strains, distinguished by sequence variation in the EBNA2 and EBNA3 genes. African populations show a higher prevalence of Type 2, which exhibits reduced B-cell transformation capacity but enhanced immune evasion (Chang et al., 2009).

Studies from Uganda, Nigeria, and Tanzania have also identified unique LMP1 polymorphisms—notably a 30-bp deletion that enhances NF-κB signalling and anti-apoptotic activity (Banko et al., 2021). Such mutations may explain the aggressiveness of EBV-associated lymphomas in African children.

Moreover, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of African EBV isolates reveals extensive recombination and regional clustering, with potential implications for vaccine development targeting LMP1 or EBNA epitopes.

Co-factors and Immune Interactions

EBV-related oncogenesis in Africa is potentiated by chronic immune activation from malaria, HIV infection, or malnutrition. Malaria-induced polyclonal B-cell activation increases the pool of EBV-infected cells, while HIV-related immunosuppression impairs T-cell control of EBV latency (Englund et al., 2011).

These co-factors underscore the complexity of virus–host–environment interactions, making molecular surveillance essential for understanding EBV disease dynamics in African settings.

HEPATITIS B VIRUS (HBV): GENOMIC VARIANTS AND LIVER CANCER IN AFRICA BURDEN AND TRANSMISSION DYNAMICS

HBV infection is hyperendemic in sub-Saharan Africa, with prevalence rates ranging from 8% to 20% in many countries. Chronic HBV infection is the leading cause of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), accounting for over 60% of liver cancers in West and Central Africa (Kramvis, 2014).

Transmission occurs predominantly through perinatal and early childhood exposure, with limited access to screening, vaccination, and antiviral therapy amplifying long-term infection rates.

Molecular Characteristics

HBV has a partially double-stranded DNA genome (~3.2 kb) with four overlapping open reading frames (S, C, P, X). The reverse transcription mechanism used for replication introduces frequent mutations, resulting in high genetic variability despite its DNA nature.

This variability has led to classification into ten genotypes (A–J) and multiple subgenotypes. In Africa, genotypes A, D, and E dominate, with genotype E being unique to West Africa and associated with rapid spread but limited global diversity (Kramvis, 2014).

Genotype-Specific Clinical and Molecular Features

- Genotype A1 (Southern and Eastern Africa): Linked to higher HBV DNA levels, increased integration into host genomes, and elevated HCC risk.

- Genotype E (West Africa): Displays low sequence diversity, suggesting a relatively recent emergence, but contributes to early-onset liver cancer.

- Genotype D (North Africa): Associated with lower response to interferon therapy.

Mutations in the precore (G1896A) and basal core promoter (A1762T/G1764A) regions suppress HBeAg expression, facilitating immune evasion and chronicity (Lamontagne et al., 2016). Additionally, surface gene mutations (notably in the “a” determinant) give rise to vaccine escape variants, which can persist even in vaccinated individuals.

Molecular Diagnostics and Therapeutic Relevance

Modern molecular assays—qPCR, sequencing, and digital droplet PCR—enable quantification of viral load, mutation profiling, and genotypic resistance testing. In African laboratories, however, limited access to sequencing technologies and standardised databases remains a barrier to personalised HBV management.

Molecular surveillance can help identify drug-resistant polymerase mutations and guide antiviral selection, improving treatment outcomes for chronic HBV carriers.

INTEGRATIVE MOLECULAR INSIGHTS: CROSS-VIRUS PATTERNS AND CO-INFECTION DYNAMICS

Africa’s viral cancer landscape is shaped not just by individual pathogens, but also by complex interactions between multiple viruses and host genetics. For example, HPV–HIV co-infection accelerates cervical carcinogenesis by impairing immune clearance, while EBV–malaria co-infection drives Burkitt lymphoma proliferation.

Figure 2: Synergistic Pathogenesis of Co-infections in Cancer Patients.

Molecular studies reveal shared patterns:

- Viral integration hotspots in cancer-related host genes (e.g., MYC, TERT, TP53).

- Persistent activation of inflammatory and immune signalling pathways (e.g., NF-κB, STAT3).

- Epigenetic reprogramming of host chromatin, sustaining viral latency and oncogenesis (Banko et al., 2021; Lamontagne et al., 2016).

Understanding these cross-viral molecular mechanisms is essential for designing pan-viral diagnostic assays and multifactorial intervention strategies suited to African populations.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS AND THE FUTURE OF MOLECULAR ONCOLOGY IN AFRICA

Diagnostic Innovations

Molecular characterisation underpins the development of sensitive nucleic acid–based diagnostics capable of detecting specific viral genotypes and oncogenic mutations. For HPV, multiplex PCR and hybrid capture assays can identify multiple high-risk variants in one test. For HBV, genotypic resistance testing improves therapeutic monitoring.

Emerging technologies like CRISPR-based detection (SHERLOCK, DETECTR) and nanopore sequencing offer potential for portable, real-time viral genomics, especially in resource-limited African laboratories.

Implications for Vaccines and Therapeutics

Molecular data can refine vaccine formulations by including regionally prevalent genotypes and predicting immune escape mutations. For instance, inclusion of HPV35 and HPV45 antigens could improve vaccine efficacy in sub-Saharan Africa. Similarly, understanding HBV genotype-specific resistance can guide next-generation antivirals and therapeutic vaccine designs.

Strengthening Genomic Surveillance Networks

African initiatives such as the H3Africa Consortium, Africa CDC’s Pathogen Genomics Initiative, and ACEGID (Nigeria) are pioneering viral genomic surveillance. Expanding these collaborations into oncology-focused molecular research will ensure comprehensive viral cancer mapping across the continent.

Regional data-sharing platforms could also support precision oncology programs, allowing clinicians to correlate viral genotype with tumour phenotype, treatment response, and prognosis.

CONCLUSION

Africa’s battle with virus-driven cancers is both a biomedical and molecular frontier. HPV, EBV, and HBV have long been recognised as oncogenic agents, but only now are we beginning to understand the depth of their molecular diversity and clinical significance within African populations.

The future of cancer control in Africa lies not only in vaccines and early detection but also in molecular research capacity—sequencing, bioinformatics, and translational genomics. By building these capabilities, African scientists can generate homegrown genomic data, design locally optimised diagnostics, and inform global precision medicine from an African perspective.

The continent’s rich viral diversity, once a challenge, could now become a scientific asset, illuminating pathways of oncogenic evolution and contributing to a more inclusive understanding of cancer biology worldwide.

REFERENCES

Chen, A. A., Gheit, T., Franceschi, S., Tommasino, M., Clifford, G. M., & IARC HPV Variant Study Group (2015). Human Papillomavirus 18 Genetic Variation and Cervical Cancer Risk Worldwide. Journal of virology, 89(20), 10680–10687. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01747-15

Cornet, I., Gheit, T., Iannacone, M. R., Vignat, J., Sylla, B. S., Del Mistro, A., Franceschi, S., Tommasino, M., & Clifford, G. M. (2013). HPV16 genetic variation and the development of cervical cancer worldwide. British journal of cancer, 108(1), 240–244. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.508

Magrath, I., Jain, V., & Bhatia, K. (1992). Epstein-Barr virus and Burkitt’s lymphoma. Seminars in cancer biology, 3(5), 285–295.

De Vuyst, H., Mugo, N. R., Chung, M. H., McKenzie, K. P., Nyongesa-Malava, E., Tenet, V., Njoroge, J. W., Sakr, S. R., Meijer, C. M., Snijders, P. J., Rana, F. S., & Franceschi, S. (2012). Prevalence and determinants of human papillomavirus infection and cervical lesions in HIV-positive women in Kenya. British journal of cancer, 107(9), 1624–1630. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.441

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Human Papillomaviruses. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2007. (IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, No. 90.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321760/

Kramvis A. (2014). Genotypes and genetic variability of the hepatitis B virus. Intervirology, 57(3-4), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1159/000360947

Lamontagne, R. J., Bagga, S., & Bouchard, M. J. (2016). Hepatitis B virus molecular biology and pathogenesis. Hepatoma research, 2, 163–186. https://doi.org/10.20517/2394-5079.2016.05

Englund, J., Feuchtinger, T., & Ljungman, P. (2011). Viral infections in immunocompromised patients. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 17(1 Suppl), S2–S5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.11.008

Münger, K., Baldwin, A., Edwards, K. M., Hayakawa, H., Nguyen, C. L., Owens, M., Grace, M., & Huh, K. (2004). Mechanisms of human papillomavirus-induced oncogenesis. Journal of Virology, 78(21), 11451–11460. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.78.21.11451-11460.2004

Ogembo, R. K., Gona, P. N., Seymour, A. J., Park, H. S., Bain, P. A., Maranda, L., & Ogembo, J. G. (2015). Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes among African women with normal cervical cytology and neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one, 10(4), e0122488. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122488

Chang, C. M., Yu, K. J., Mbulaiteye, S. M., Hildesheim, A., & Bhatia, K. (2009). The extent of genetic diversity of Epstein-Barr virus and its geographic and disease patterns: a need for reappraisal. Virus research, 143(2), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2009.07.005

WHO (2023). Cancer Fact Sheet: Africa Region. World Health Organization.

Okoye, J. O., Ofodile, C. A., Adeleke, O. K., & Obioma, O. (2021). Prevalence of high-risk HPV genotypes in sub-Saharan Africa according to HIV status: a 20-year systematic review. Epidemiology and health, 43, e2021039. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2021039

Young, L. S., & Rickinson, A. B. (2004). Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nature Reviews. Cancer, 4(10), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1452

Banko, A., Miljanovic, D., Lazarevic, I., & Cirkovic, A. (2021). A Systematic Review of Epstein-Barr Virus Latent Membrane Protein 1 (LMP1) Gene Variants in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland), 10(8), 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10081057