- Authors: Anthony Olayemi, Obidi Nwasoluchukwu, Ekpunobi Nzube, Tunde Animashaun

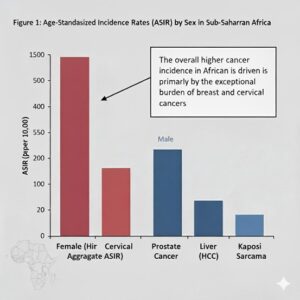

- Cancer constitutes a rapidly escalating public-health crisis throughout the African continent, marked by significant sex-based differences in incidence, access to care, and survival outcomes. Aggregate age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs) in sub-Saharan Africa are currently higher among women than men, a pattern driven primarily by the profound burden of breast and cervical cancers (Ferlay et al., 2022). Despite this higher incidence among women, overall outcomes are universally poor for both sexes, stemming from a confluence of factors including late-stage diagnosis, critically limited treatment infrastructure (radiotherapy, surgical oncology), and pervasive social and structural barriers that are often gender-specific. Furthermore, substantial data deficits, characterized by incomplete cancer registries and diagnostic limitations, obscure the true magnitude of the crisis and hinder effective, localized policy development (Adewole et al., 2023). Addressing this disparity requires urgent, multi-faceted action focused on fortifying cancer surveillance, scaling up cost-effective primary prevention (e.g., HPV vaccination), improving early detection, expanding access to affordable, quality treatment modalities, and systematically dismantling gendered impediments to care, such as financial dependence, care giving burdens, and health-related stigma (Parkin et al ., 2016; Ngwa et al., 2022).THE CHALLENGE OF DATA GAPS

- It is critical to acknowledge that many continental summaries rely on modeled estimates due to the persistently incomplete population-based cancer registry coverage across vast regions of Africa. While these models are invaluable, they introduce uncertainty, particularly in sex-specific and sub-regional trend analysis. Where possible, statements are grounded in data from AFCRN-supported, registry-based analyses and detailed country-level studies to enhance validity (Adewole et al., 2022).PATTERNS OF INCIDENCE BY SEX

- Overall Continental Pattern

- Recent GLOBOCAN statistics indicate a significant increase in the absolute count of new cancer cases in Africa, surpassing one million diagnoses in 2020, with projections for continued steep rise in the 2020s (Ferlay et al., 2022). Unlike many high-income regions where male ASIRs typically exceed female rates, aggregate data for sub-Saharan Africa show a slightly higher age-standardized incidence for women (Ginsburg et al., 2017). This unusual demographic pattern is predominantly attributed to the exceptional burden imposed by high-incidence, female-specific cancers, namely breast and cervical carcinoma.

Figure 1: Age-Standardized Incidence Rates (ASIR) by Sex in Sub-Saharan Africa

Major Cancers Driving Female Burden

Breast Cancer:This is the most prevalent malignancy among African women by incidence (Ferlay et al., 2022). The rise in incidence is linked to rapid urbanization, increasing prevalence of obesity, shifts in reproductive patterns (e.g., later childbearing, fewer children), and, in some settings, improved, though still limited, detection (Ssentongo and Ngufor, 2022). Outcomes are frequently compromised because a large proportion of women present with locally advanced or metastatic disease.

- Cervical Cancer:This remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women in numerous African nations (Sung et al., 2020). This high burden is a direct consequence of high Human Papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence, coupled with severely limited access to organized screening programs and low coverage of primary prevention through HPV vaccination (Bruni et al., 2023).

Major Cancers Contributing to Male Burden

- Prostate Cancer:This cancer represents a high-incidence, high-mortality concern in many African male populations, with notable increases documented in established registry analyses (Ucheya et al., 2020). However, significant variability exists across countries in detection practices and reporting quality.

- Infection-Related Cancers:Cancers such as Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC, or liver cancer), Oesophageal Cancer (OC), and Kaposi Sarcoma (KS) contribute substantially to the male cancer burden in several regions (Ferlay et al., 2022). (Sung et al., 2020). The etiologies of these cancers are closely linked to infections (e.g., Hepatitis B/C viruses, HIV, HPV) and other environmental and lifestyle exposures (e.g., alcohol, tobacco).

Sex Ratio Differences

Cancers associated with smoking, heavy alcohol use, and certain environmental exposures (e.g., Lung, Liver, Oesophageal) generally demonstrate a male predominance (Ferlay et al., 2022). However, the overwhelming relative contribution of the female-specific cancers—specifically breast and cervix—in many African epidemiological settings shifts the overall continental sex balance of cancer incidence toward women, in contrast to patterns observed in most high-income countries.

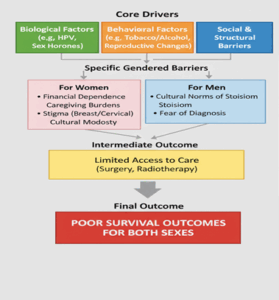

DETERMINANTS OF SEX DIFFERENCES: BIOLOGICAL, BEHAVIORAL, AND STRUCTURAL

The observed gender disparities in cancer outcomes are a result of complex interactions between biological factors, sex-specific risk behaviors, and fundamental social and structural determinants.

Biological and Exposure Drivers

The inherent biological differences, particularly concerning sex-specific tissues and oncogenic infections, are primary drivers. HPV is the necessary cause of cervical cancer (female-specific), while sex hormones profoundly influence breast and prostate cancer risks (Ucheya et al., 2020).. The distribution of infection-related cancers, such as HCC (HBV/HCV) and AIDS-defining malignancies (HIV/AIDS), is heavily modulated by the gender-specific patterns of exposure, transmission, and access to and adherence to treatment (Sung et al., 2020).

Behavioral and Environmental Exposures

While tobacco and alcohol use have historically been higher among men, rates are escalating in some specific female sub populations, impacting the gender gap in cancers such as lung, oesophageal, and liver cancers (Ngugi et al., 2020). For women, reproductive and metabolic changes associated with urbanizing lifestyles such as later age at first birth, reduced parity, lower rates of breastfeeding, and increased rates of obesity are well-established factors influencing the rising incidence of breast cancer (Ssentongo et al., 2022)

Social and Structural Determinants

These non-biological factors are crucial in explaining differences in access, stage at presentation, and survival.

One of them is the health-seeking behavior of both genders. Gendered social norms dictate when and how individuals engage with healthcare. Women frequently experience delays due to caregiving obligations, limited financial autonomy, or high perceived costs. Conversely, male delays can be linked to cultural norms of stoicism or fear of a potentially debilitating diagnosis (Nambooze et al., 2016).

Another is financial dependency and catastrophic Costs with regards to healthcare. Cancer diagnosis and treatment often necessitate substantial out-of-pocket payments in Nigeria. Women, who frequently possess lower earning power and financial control, are disproportionately vulnerable to the resulting catastrophic health expenditures, critically hindering their ability to initiate and complete necessary treatment (Nambooze et al., 2016).

Also, stigma and misinformation is a tremendous social constraint as cancers affecting the reproductive or sexual organs (e.g., cervical, breast) often carry significant social stigma, which acts as a powerful deterrent to early presentation and screening uptake (Jedy-Agba et al., 2018).

Figure 2: Gendered Determinants of Cancer Disparities in Africa

ACCESS TO DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

The entire oncology care continuum is severely constrained by widespread shortages in surgical oncology capacity, radiotherapy units, and the availability of affordable systemic therapies (Ssentongo et al., 2022). Even where services exist, the ancillary barriers of transportation, accommodation for multi-week treatments, and costs create distinct gendered barriers, often preventing women from undertaking treatment without significant household support.

Late stage at presentation is a widespread challenge for both sexes across Africa, but the underlying mechanisms are gendered (Jedy-Agba et al., 2018).

For women, delays are frequently tied to a lack of awareness, cultural barriers concerning modesty/disclosure, and severely limited access to preventative screening, such as for cervical cancer. The resulting advanced-stage diagnoses are a primary driver of the poor survival statistics observed continent-wide (Sung et al., 2021).

HPV Vaccination represents the single most game-changing preventative intervention for cervical cancer. However, rollout and sustained uptake remain uneven across the continent. Scaling up comprehensive HPV vaccination, alongside affordable and effective screening methods (such as visual inspection with acetic acid or HPV testing), offers the clearest path to dramatically reducing female cancer mortality (Ssentongo et al., 2022).

Figure 3: HPV Vaccination as a Primary Prevention Strategy

SURVIVAL OUTCOMES AND MEASURED GAPS

Survival estimates consistently demonstrate that the 5-year survival rates for most cancers in sub-Saharan Africa are substantially lower than those achieved in high-income countries (Jedy-Agba et al., 2018). For example, a pooled 5-year survival estimates for breast cancer in the region have historically hovered around 40% but show improving trends, with significant variability among countries and registries (Ssentongo et al., 2022).

Survival differences by sex are cancer-specific: in some analyses, males experience poorer survival for cancers such as oesophageal or lung cancer (Sung et al., 2021). The key factors contributing to uniformly poor survival are: late-stage diagnosis, limited access to guideline-concordant treatment, frequent treatment interruptions, and high rates of comorbidities (including HIV) (Jedy-Agba et al., 2018). These factors are inextricably linked to the gendered social determinants (financial barriers, stigma, caregiving) that exacerbate treatment delays and non-adherence, thereby producing differential, and often worse, outcomes.

However, there is a foundational challenge of the lack of comprehensive national population-based cancer registries (PBCRs) in many African countries (Ngwa et al., 2023). While the AFCRN plays a vital role in supporting regional registries, the patchy coverage severely limits the ability to conduct precise, sex-disaggregated measurements, track epidemiological trends accurately, and inform evidence-based resource allocation.

A transparent, concerted effort to strengthen and expand operational PBCRs is an essential prerequisite for evidence-based policy.

POLICY, PROGRAM, AND INTERVENTION EVIDENCE

Evidence-based interventions offer clear pathways to mitigating gender disparities in cancer.

One of the fundamental strategy is prevention and vaccination. Universal HPV vaccination for pre-adolescent girls (with consideration for boys where economically feasible) has the highest long-term impact potential for drastically reducing the cervical cancer burden. Successful, large-scale country rollouts, such as in Rwanda, demonstrate the feasibility of well-funded and politically supported programs (Saura-Lázaro et al., 2023).

Also, the implementation of low-cost screening methods (e.g., visual inspection with acetic acid, affordable HPV testing) coupled with strong, assured linkage to treatment for pre-invasive and early invasive disease can significantly reduce mortality (Bruni et al ., 2023). Successful uptake is contingent upon community awareness campaigns and the provision of female-friendly, accessible services that respect cultural norms.

There is also an urgent need for multi-sectoral investment in: decentralized surgical services, reliable maintenance and expansion of radiotherapy capacity, and pooled procurement mechanisms to secure affordable systemic therapies (including generics and biosimilars) (Jedy-Agba et al., 2018). Task-sharing—training non-specialist clinicians (e.g., nurses, general practitioners) to undertake specific oncology tasks—and utilizing telemedicine can effectively bridge the critical gap created by specialist scarcity (Parkin et al., 2016).

RESEARCH GAPS AND PRIORITIES

To accelerate progress, research efforts must be strategically directed. This includes:

High-Quality Data Infrastructure: Prioritize the expansion and sustenance of sex-disaggregated, population-based cancer registry data across more nations to enable accurate incidence and survival comparisons (AFCRN expansion is critical).

Implementation Science: Conduct rigorous implementation research to evaluate gender-sensitive interventions designed to increase screening uptake and early diagnosis among both women and men.

Economic Analyses: Undertake detailed economic studies quantifying the gendered catastrophic costs of cancer care and evaluate the cost-effectiveness of mitigation strategies.

Translational Biology: Investigate potential distinctions in tumour biology (e.g., aggressive breast cancer subtypes) within African populations and how these biological realities intersect with gender and structural barriers to inform tailored treatment protocols.

CONCLUSION

Gender disparities in cancer across Africa are a function of complex, intertwined biological, behavioral, and, most powerfully, structural and social determinants. While women in many settings bear a disproportionately higher burden of cancer incidence due to cervical and breast cancers, both women and men face profound, life-threatening obstacles to timely diagnosis and efficacious treatment. Closing the survival gap is an ambitious but achievable objective that hinges on a dual strategy: strengthening data systems and scaling up proven prevention measures (HPV vaccination, tobacco control), while simultaneously investing in accessible, affordable, quality diagnostic and treatment services that are specifically designed to overcome deeply ingrained gendered social and economic barriers. Intersectoral action, engaging ministries of health, education, finance, and social protection, is essential for this complex public-health challenge.

REFERENCES

- Bruni, L., Saura-Lázaro, A., Montoliu, H., Serradell, L., Vallès, X., Moreno, M., de Sanjosé, S., Bosch, F. X., & Brotons, M. (2023). HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening in Africa: Challenges and opportunities. Infectious Agents and Cancer, 18(1), 3.

- Ferlay, J., Ervik, M., Lam, F., Colombet, M., Mery, L., Piñeros, M., Znaor, A., Soerjomataram, I., & Bray, F. (2020). Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://gco.iarc.who.int/today

- Ginsburg, O., Bray, F., Coleman, M. P., Vanderpuye, V., Eniu, A., Kotha, S. R., Sarker, M., Huong, T. T., Allemani, C., Dvaladze, A., Gralow, J., Yeates, K., Taylor, C., Oomman, N., Krishnan, S., Sullivan, R., Kombe, D., Blas, M. M., Parham, G., … Conteh, L. (2017). The global cancer survival gap: A call for action. The Lancet, 390(10107), 1848–1857.

- Jedy-Agba, E., Joko-Fru, W. Y., Dareng, E. O., Adebamowo, C. A., Odutola, M., Oga, E. A., Fabowale, T., Igbinoba, F., Omonisi, A., Otu, T., Korir, A., Wabinga, H., Chokunonga, E., Somdyala, N., Chen, W., Ogunbiyi, O. J., & Parkin, D. M. (2018). The African Cancer Registry Network (AFCRN): Progress and challenges. Cancer Epidemiology, 57, 126–133.

- Ngugi, A. K., Wanzala, P., & Ochieng, J. (2020). Socioeconomic and geographic inequalities in breast and cervical cancer screening in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiology, 68, 101783.

- Ngwa, W., Addai, B., Adewole, I., Adebamowo, C., Asante-Shongwe, K., Boehmer, L., Bowering, J., Brown, R., Ddumba, E., Denny, L., Githanga, J., Gopal, S., Gueye, S. M., Haar, G., Hanna, T. P., Jedy-Agba, E., Krishnan, S., Leys, C., Moka, D., … Zubizarreta, E. (2022). Cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: A Lancet Oncology Commission. The Lancet Oncology, 23(8), e387–e435.

- Parkin, D. M., Nambooze, S., Wabinga, H., & Ngoma, T. (2016). Diagnosis and treatment of cancer in Africa. International Journal of Cancer, 138(2), 292–301.

- Ssentongo, P., Ngufor, C., Ssentongo, A. E., Oh, J. S., Oh, T., Ericson, J. E., & Chinchilli, V. M. (2022). Breast cancer mortality and incidence trends in sub-Saharan Africa: An age–period–cohort analysis. BMC Cancer, 22(1), 318.

- Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(3), 209–249.

- Saura-Lázaro, A., Bock, P., Bogaart, E. V. D., van Vliet, J., Granés, L., Nel, K., Naidoo, V., Scheepers, M., Saunders, Y., Leal, N., Ramponi, F., Paulussen, R., de Wit, T. R., Naniche, D., & López-Varela, E. (2023). Field performance and cost-effectiveness of a point-of-care triage test for HIV virological failure in Southern Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 26(10), e26176.

- Ucheya, S. O., Nwokoro, I. U., & Ndukuba, C. A. (2020). Prostate cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: Incidence, presentation, and challenges. World Journal of Clinical Oncology, 11(9), 661–671.